GRAMMY AWARDS 1977

DESTINY

DAGENS BILD

-

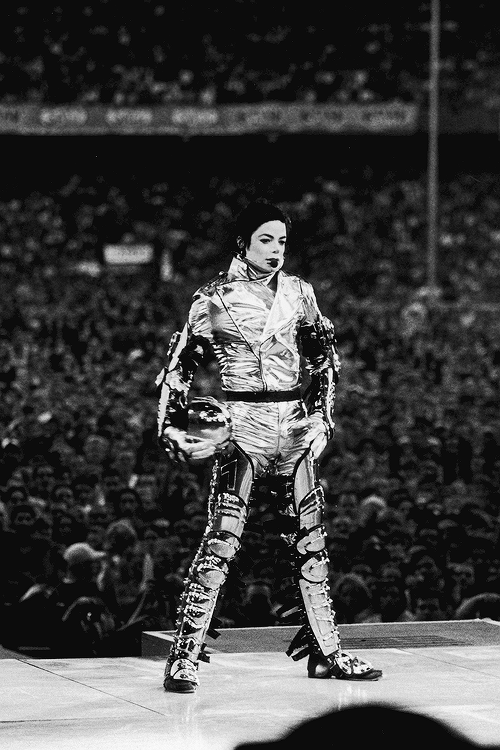

THE QUINTESSENTIAL ENTERTAINER

DAGENS BILD

"MICHAEL MCKELLAR"?

Song Info: (MJJC/PositivelyMichael)

Michael McKellar - Written in 1990/1 - Failed to make the Dangerous album.

“Michael McKeller lives in a different world.

Oh what a different.

NOBODY seems to care.

Waits at the window, look how he’s lying there

pretends he’s dying there. NOBODY seems to care.

Isnt it clear nobody noticed, serving his heart on a tray now.

Isnt it queer look and you’ll notice bowing his head.

Talks to the mirror, he’s standing in the rain.

Tries to escape the pain, his pain remains the same.

Talks to the mirror, feels he must run away to pray now, away now.

Nothing’s for Christmas.

Fighting, trying to hide his fears, crying but noone hears.

Inside he hides the tears.

Feels he must run away.”

Frank Cascio: Traveling the world with Michael Was an adventure. He loved staying in Hotels, He instantly made them his mini Home. Every hotel we stayed in, we had to use aliases. Some of them, I have to say were quite funny. “Donald Duck” “Captain Hook” “Mr Green” “Homer Simpson” Bart Simpson” He would also stay under the name “Michael McKeller” Which is the title to one of his songs. I think my Favorite one was when we all became the “Potter Family” Michael was Harry Potter, I was Frank Potter.…”I liked “Turning Me Off”, an up-tempo song that hadn’t made it on to the Dangerous album; a song called “Chicago 1945” about a girl who went missing a pretty song called “Michael McKellar” and a song that eventually came out on Blood On The Dance Floor called “Superfly Sister”.

TIME WAITS FOR NO ONE

-

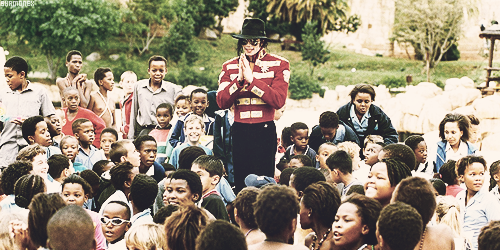

A VOLUNTEER!

-

FOX NEWS INTERVIEW 2002

SERIOUS EFFECT (DEMO)

FALL AGAIN (DEMO)

CHEATER (DEMO)

MICHAEL ON THE PHONE

HE WAS HIS MUSIC

PRODUCING MICHAEL JACKSON

Piers Morgan: Of all the things that you’ve experienced in your extraordinary career and life, If I could give you 5 minutes to replay one of them again, what would it be?

Lenny Kravitz: A career moment, wow. You know, I’ve had so many where I had to pinch myself… Probably producing Michael Jackson. And there’s been a lot of great ones but that was something extraordinary

PM: What made is so extraordinary?

LK: Well, the fact that I wouldn’t be here today if I hadn’t seen the Jackson 5 when I was 6 years old. That was the 1st concert I’d ever been to, my father took me to Madison Square Garden to see them. And it changed everything. The universe was a different place the next day, I was completely blown away by the music, the talent, the whole experience. And here I am in the studio, I’ve written a song for Michael and he’s standing there telling me to be very hard on him: ‘I wanna do this exactly the way you see it, so stop me every time it’s not the way you want it and we’re just getting into it and working together and spending a week together in the studio and it was just unbelievable.

PM: What kind of man was he? For real

LK: First of all, just a beautiful being, extremely professional, a perfectionist. Still having the passion all those years later. You know, he would work all day and night, come back the next day, all day and night. He hand’t lost that… A great father, he was amazing with his children, I spent time with the kids and we were all in the studio so they would come and we would all hang out together, he was a very good father. And he was funny! Very funny, he laughed all the time… And he could eat more than you think

PM: He was an incredible talent

LK: Yeah, the greatest ever, I would agree with that

PM: How did you feel when you heard what had happened to him?

LK: I was obviously devastated, I was blown away, I found out on stage in Scotland as I was coming off and getting ready to go back on and they told me, and I had to go back out. It’s extremely sad, I was really looking forward to seeing him come back and do those shows. Even though I knew… wow 50 shows, that’s very serious.

PM: Do you think of our lifetime Michael Jackson was the best?

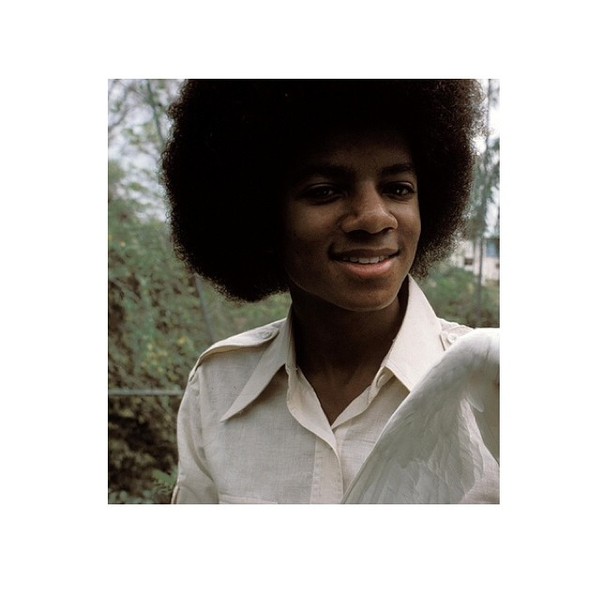

LK: Of course, you can’t touch him. And people think about Michael Jackson in his solo career, which is obviously phenomenal but the deepest genius I saw on him was when he was a child; he was a child that sang with the same talent soul and intensity of Aretha Franklin or James Brown or any great vocalist.

-Piers Morgan interview: Lenny Kravitz about Michael Jackson (2011)

TATTOO

RADIO INTERVIEW 1973

-

DAGENS BILD

-

MIMMI PIGG

LOVING YOU, THAT'S WHAT I WANT TO DO

-

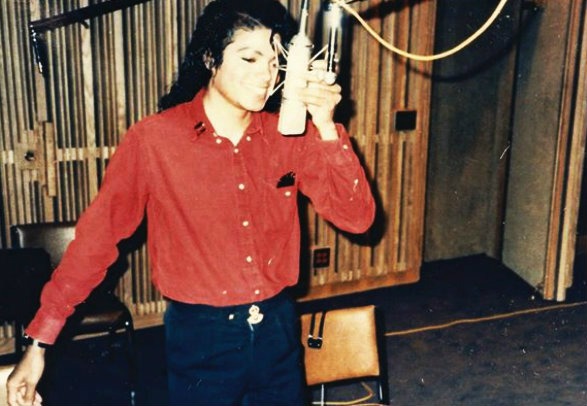

IN THE STUDIO

SEE

Ebony: Any Black ladies in your life?

Michael: “Sure, but you wouldn’t take me seriously.”

Ebony: Try me.

Michael: “It’s Diana Ross. I love her.”

Ebony: Do you mean as a “big sister?”

Michael: “No, that’s not what I mean. See, I told you that you wouldn’t take me seriously.”

Ebony: You’re not saying you’d like to marry Diana Ross, are you?

Michael: “Oh yeah, I’m saying that.”

Ebony Magazine 1984

-

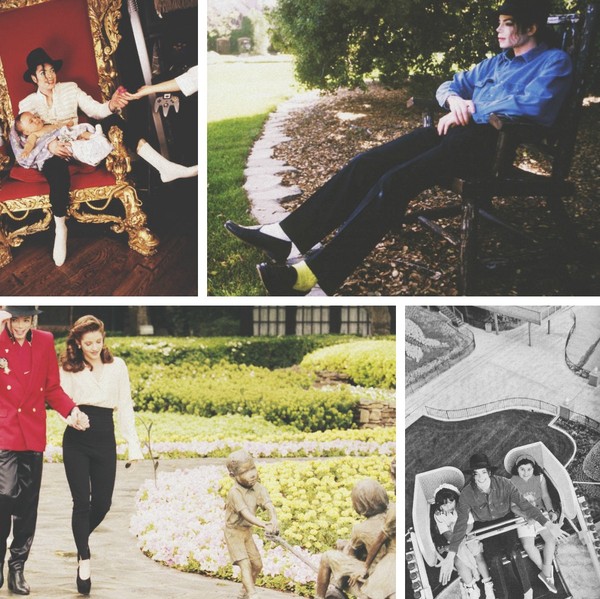

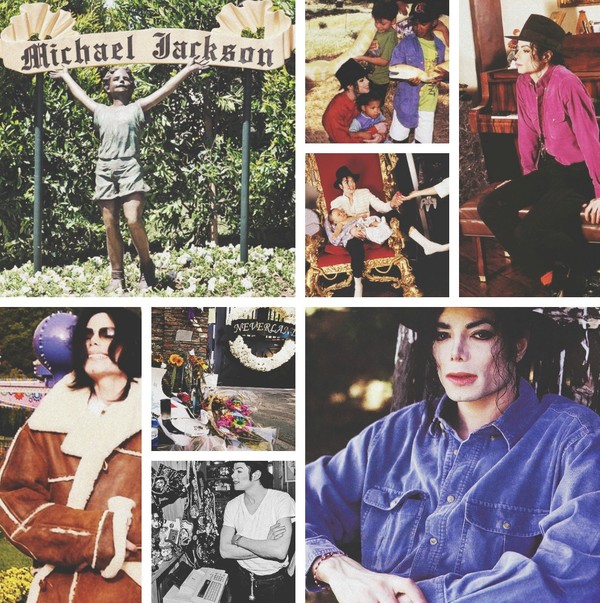

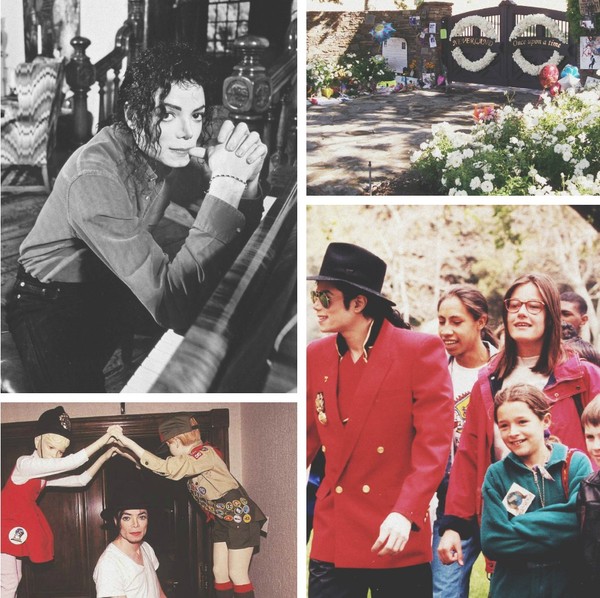

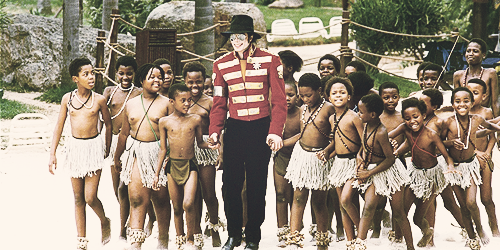

TAKE MY HAND, AND COME TO NEVERLAND

ARMBAND

-

BEN

F.D. LIVVAKT TILL MICHAEL

FANTASTISKA NEVERLAND

-

-

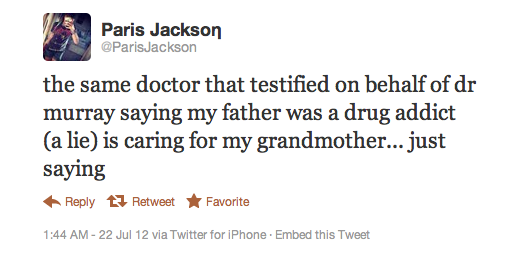

A LIE

DAGENS BILD

-

SINGING

SKUM?

INTERVJU STUDIO 54, 1978

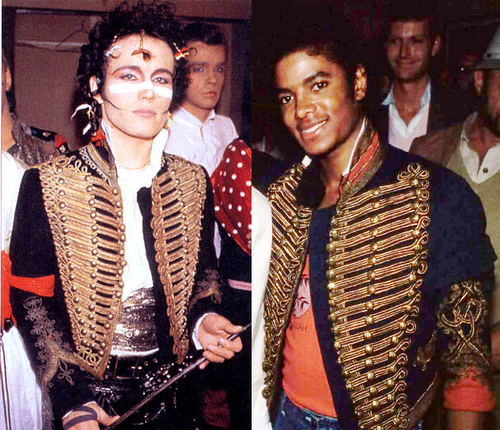

ADAM ANT RECALLING MOMENTS WITH MICHAEL

The ringing of a telephone cut sharply through my sleep. I fumbled for the receiver.

'Hello?' A soft, highpitched voice echoed down the line to me.

‘Hello,’ it repeated. ‘Is that Adam Ant?’

The voice had an American accent and sounded vaguely familiar, but my fuzzy brain reacted angrily.

‘Terry,’ I said, thinking it was one of the Ants’ drummers playing a prank. ‘Stop p****** about. It’s 4am and I’m trying to sleep.’

‘No, it’s not Terry,’ said the voice. ‘It’s Michael. Is that Adam Ant?’ ‘Very funny, Terry, now f*** off.’ I slammed the phone down, rolled over and tried to get back to sleep.

The phone went again. ‘Hello,’ I barked into the receiver. ‘Hi, no, really, it is me, Michael Jackson,’ said the funny voice, ‘and I just want to ask you…’ ‘Terry, if you don’t stop this I’m going to come over there and f****** thump you.’ Bang. Again the phone went down.

Again I rolled over. Again the phone rang. I grabbed the receiver and shouted: ‘Terry! That’s IT!’

‘Er, hi, is that Adam Ant?’ This time the voice was deep, sonorous, American and calm. It didn’t sound anything like Terry. ‘Oh, oh,’ I stammered.

‘Yes, this is Adam. Who are you?’ ‘I’m Quincy Jones, calling from LA. Sorry, we probably woke you, but I’m here with Michael Jackson and he’d like to speak with you. Is that OK?’ A pause, and then that same soft voice. ‘Hi, Adam, it’s Michael. Sorry if we woke you.’

‘Oh, no, sorry to have been so rude,’ I apologised. He said he had just seen the video for our song Kings Of The Wild Frontier. ‘It’s great,’ he said. ‘How did you get the tom-tom sound?’ ‘Oh, thanks. Well, we use two drum kits and then add loads of other percussion on top…’

‘That’s great, Adam,’ Michael interrupted. ‘I really like your jacket. Where’d you get it?’

'Huh? My jacket?' I tried to think. 'Berman's and Nathan's in London's Covent Garden. They supply costumes for movies.'

'Wow. That's great,' he replied. 'How do you spell that? Bowman's and who?' 'No, B-E-R-M-A-N-apostrophe-S and N-A-T-H-A-N-apostrophe-S.'

‘Great, thanks. Let’s meet up next time you’re in America, huh? Bye.’

The line went dead.

-

´94 NAACP IMAGE AWARDS

9/12/14

VACKRASTE

<3

CIRQUE DU SOLEIL HYLLAR "A PLACE WITH NO NAME"

DAGENS BILD

I AFRIKA

8 SEPTEMBER

LIKE

AMERICA'S NEXT TOP MODEL

-

MICHAELS FÖDELSEDAGSFIRANDE I GARY, INDIANA

BEHIND THE SCENES "BLACK OR WHITE"

SMASH

“You’re not gonna believe it—Michael’s got a little platform that he dances on, right there in the studio. He’s doing all kind of moves while he’s recording his vocals!”

That was the first thing photographer Bobby Holland, my roommate at the time, told me when he returned to our mid-city Los Angeles apartment one evening in 1978 after spending some time at Allen Zentz Recording, a nondescript studio in Hollywood, where Michael Jackson was recording the Epic/CBS solo album with producer Quincy Jones that would become the iconic Off The Wall.

Holland was hired by our friend Ed Eckstein, who then ran Quincy Jones Productions, to shoot casual, not-posed photos of Jackson and Jones working in the recording studio, for publicity purposes.

You read correctly—publicity. Back then, Michael and Quincy, while accomplished and famous, weren’t cultural icons. In fact, both were at stations in their careers where they had something to prove. Entering his twenties, Michael wanted to create an album that reflected who he’d become musically.

Quincy, while renown as a bandleader, award-winning arranger, producer, composer and soundtrack scorer, was looking to solidify his reputation as a mainstream producer. Yes, he’d produced his first hit single in 1963 with Lesley Gore’s pop classic, “It’s My Party” and in the ‘70s produced hits by Aretha Franklin, the Brothers Johnson, Rufus & Chaka Khan, as well as his own albums. But in the ’70s he wanted to be seen as a certified hit maker.

Executives at CBS Records (which later became Sony) respected Quincy—everyone respected Quincy–but didn’t see him as the man to produce Michael Jackson. Not that they viewed Michael as invaluable; at that time, he was just another artist.

But to produce Michael they preferred someone like Maurice White–founder/producer of the label’s biggest black band, Earth, Wind & Fire–who’d also had success producing Deniece Williams, keyboardist Ramsey Lewis and the Emotions.

Even the Jacksons had ideas about who should produce Michael’s solo album. They felt they should do it, and told Michael as much in front of me one afternoon in September 1977.

Jackie, Tito, Marlon and Randy and I were sitting on a leather sectional in the den of the family’s original ranch style Encino home on Hayvenhurst (before Michael had it demolished and built the new mock tudor mansion) while a Sanyo Ghetto Blaster on the coffee table blared instrumental tracks–no lead or background vocals yet–from Destiny, the first album, save the track “Blame It On The Boogie,” that they’d been allowed to write and produce themselves.

Michael was sitting on a wooden chair across from us, making the occasional rhythmic movement to the music. It was something to behold–Michael Jackson dancing in his seat–but I did so through my peripheral vision, for fear that if I simply looked, he’d become self-conscious and stop.

“We been waiting to produce our own stuff for a long time, man,” Jackie proudly said, when the cassette ended. “After this album, Michael’s doing a solo record. He’s talking to different people, but he’s thinking about keeping it in the family and letting us produce HIS album, too. Right Mike?”

Michael looked away, as if he didn’t really hear it, his silence speaking volumes.

In any case, it was through Holland, Eckstein and Quincy Jones himself that I was unwittingly afforded a front row seat to the creation of what arguably ended up the most important album of Michael Jackson’s solo career. When Bobby returned to our apartment that evening from the studio, I grilled him for details.

“Well, he was laidback and quiet about everything but the music,” Bobby said of Michael, while reaching into the fridge for a beer. “Quincy did have him laughing at some of that shit he says—you know how Quincy is, always telling stories—but it was when the music started that Mike turned into a tiger. While singing, he’d actually be doing a lot of the shit he does on stage, like a mini-concert. It was a trip.”

Some days there wouldn’t be enough light in the room for Bobby to take photos–when Michael was behind the mic singing, the singer insisted the studio be dark. “The only lights in the room,” said Bobby, “were on the recording console and the light on the music stand with the lyrics on a piece of paper in front of Michael.”

It was a no-frills operation. No limos, no elaborate security detail, no chef-catered gourmet meals. Quincy doesn’t drive, so at about noon he would arrive at the studio driven by a man behind the wheel of Quincy’s car, “a regular ol’ Buick.”

A Buick, Bobby? You sure?

“Hey, my daddy was a Buick man. I know a Buick when I see it. It was a Buick.”

According to Bobby, Quincy carried a briefcase that, when Quincy opened it, contained music charts and…a bottle of hot sauce. They’d order lunch and dinner from menus of places nearby, but Q had to have his own hot sauce.

Michael would arrive shortly afterward, someone driving him, too. “Not Bill Bray, though (the longtime Jackson family security man),” said Bobby. “Some other guy.”

One day Michael showed up dressed like actor Charlie Chaplin. “From head to toe,” Bobby said. “Make-up; the whole nine. And he worked like that. Nobody made a big deal of it. Imagine Charlie Chaplin jammin’ to ‘Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough.’”

Some days, there’d be musicians, but often it would be just Michael, Quincy, Quincy’s longtime engineer Bruce Swedien and, as Bobby told me one evening after returning from the studio, “this white guy named Rod Temperton.”

I’d heard of him. A lanky, quiet chap from England who was a member of Heatwave, the monstrous interracial R&B band wearing out the top acts they opened for on the road and burning up the charts with hits like “Boogie Nights,” “The Groove Line” and the ballad, “Always and Forever.”

Temperton was a phenom—a square-looking white boy who looked as if he should have been selling insurance policies–with a simply ridiculous command of R&B grooves and a penchant for lyrics that somehow always included “hot” and “street.”

One afternoon, maybe a year before he started working with Temperton, I was hanging out at Quincy Jones’ office on the A&M Records lot with Eckstein, when Quincy, sitting behind his desk, turned serious and, asked, “Ivory, what do you think of Rod Temperton? Would the songs he writes for Heatwave translate to other artists in general?” Quincy Jones is asking my musical opinion.

“Hmmmm,” I said, thoughtfully. “I don’t know, Q. Those songs work well with that band, but…I just don’t know.”

Quincy looked at me and shook his head, as if to say, ”You’re probably right.” Obviously, the man was indulging me. Even as he asked the question, he’d already locked up Temperton in a contract.

If Michael and Quincy had something to prove with this production, without a prior collaborative success breathing down their backs, they also had the luxury of making an earnest record. Unlike later Jackson releases, Off The Wall featured no gimmicks—no rock songs meticulously designed to appeal to a demographic that wouldn’t normally listen to Jackson’s music; no star musician cameos recruited purely for show.

Rufus (as in Rufus Featuring Chaka Khan) basically served as the production’s studio band. Before Rufus’ Quincy-produced Masterjam album and Off The Wall, Rufus’ new drummer, John “JR” Robinson, hastily recruited by the band while in the midst of a tour, had never even played on a major recording session.

Singer Patti Austin was a superb duet partner for Michael during “It’s The Falling In Love,” but if that song had appeared on Thriller, chances are a bigger name would have been hired for marquee value.

During the album’s production, some evenings Eckstein would come by our apartment with a cassette of rough tracks from a week’s worth of sessions and we’d light up a joint and listen. I was taken aback. Temperton’s mighty “Burn This Disco Out” was my immediate favorite. It was a big, aggressive, glossy groove that, vocally, Michael ate alive.

It was intriguing to hear things to which the world wouldn’t be privy—like Michael’s voice cracking during the Stevie Wonder song, “I can’t help it,” as he struggled to move into an even higher falsetto register than he was already in during his ad-libs at the end of the song. Who knew Mike was anything but perfect?

When Off The Wall was released in August of 1979, Bobby and I might have been as excited as Michael. All the insight we’d gleaned into its production made its success feel personal. It was an immediate smash, ultimately selling some six million copies. (Since its release the album has sold some 20 million copies globally.)

Despite its triumph, that the album only won a Grammy Award for Best Male R&B Vocal Performance for its first single, “Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough” so upset Michael that after the ceremony, Quincy said Michael was limoed home, where he “cried himself to sleep.”

Reportedly, Michael told CBS Records CEO Walter Yetnikoff that he felt Off The Wall should have won Record Of The Year. Meanwhile, Yetnikoff was said to have told label execs that while Off The Wall’s sales were a welcome windfall, Michael’s insistence that his follow-up album would be even bigger was but an artist’s fantasy.

Of course, we all know how that worked out.

~ Steven Ivory

A FLIRT

-

FIN

DAGENS BILD

TELL ME WHAT ABOUT IT

-

INTERVJU 1970

...

JOY

ELIZABETH, I LOVE YOU

PARIS OCH OMER

DAGENS BILD

MICHAELS FÖDELSEDAGSFIRANDE I GARY, INDIANA

<3

CHILLS